Martin luther was ahead of his time – especially in defamation. No one ranted like him. The reformer was inexhaustibly creative when it came to using strong language against his opponents.

The pope, for example, was for him "the dutch father," "the jack of all trades in rome," "the shameless liar," "the deluded devil’s child," "the devil’s sow," and much more. There is now a website on which you can be insulted by luther in ever new ways at the touch of a button – unfortunately only in english translation: "ergofabulous.Org/luther/".

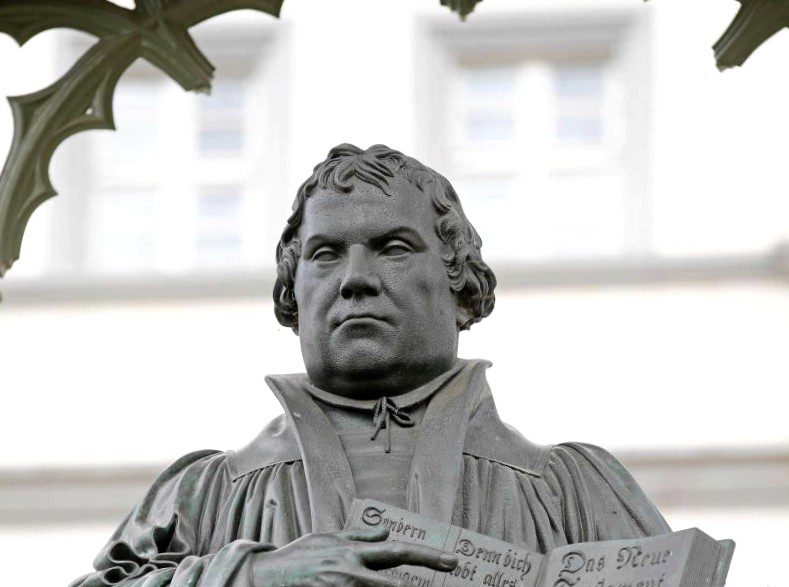

The debate he sparked, however, allowed something like publicity to emerge for the first time. "Martin luther was, after all, a best-selling author," explains tillmann bendikowski, author of the book "the german war of faith: martin luther, the pope and the consequences". Luther published his opinions in pamphlets with – by the standards of the time – enormous circulation.

The new information technology of printing changed people’s lives in a similar way to the internet today: the knowledge collected was no longer reserved for a small elite of scientists and monks, but was basically available to everyone. You only had to know how to read – or know someone who could read," he says. Printing with movable type had already been invented around 1450, but it was not until the reformation that books, pamphlets and graphics really became a mass medium. For only now was there an event that interested everyone and in which fundamentally different opinions collided. The reformation mobilized and divided public opinion.

Luther’s theses spread through the social networks of his time: they were shared – passed from hand to hand as pamphlets – and commented on – in pubs, on village squares and in new pamphlets. The tone of the public debate became increasingly sharp. The humanist erasmus of rotterdam – a true celebrity who was recognized on the street – could admonish as much as he liked that a certain level should be maintained and the theological debate should not be carried out on the street: luther did not even think about it. Its target group was "the mother in the house, the children in the streets, the common man in the market". And he spared no polemic, no shitstorm in doing so.

"The emergence of a public sphere was definitely an essential factor in the birth of the modern age," explains luther biographer and reformation expert heinz schilling in an interview with the german press agency. "But it was not luther alone who brought this about, it was also his opponents from the catholic side. It was not the reformation as such, but the dispute about it that gave rise to a public sphere. Even if we don’t like it so much today: it was precisely the conflictual nature that brought about the new."

It was for the people of the 16th century. It was a tremendous experience in the first half of the nineteenth century to be able to read the bible for oneself, thanks to luther’s german translation. Suddenly they had direct access to the "word of god", which until then the priests had always conveyed to them only in a very filtered and indirect way. "Now everyone can speak and judge of the things, since one could not know anything before", it was said in a contemporary writing. "Without question, luther provided a decisive impetus for the establishment of a new, increasingly literate public sphere," emphasizes historian bendikowski. However, the process of alphabetization in the 17. The nineteenth century was brutally interrupted by the thirty years’ war.

Even though luther did not want to abolish the church, he felt that it was no longer absolutely necessary as a mediator between god and man. "The history of the modern subject actually began with luther," says journalist ulrich greiner. "Now man was directly to god. Now he could and was allowed to "me" say."

This changed the self-image of the human being. Historian schilling, however, concedes: "individualization and secularization were long-term processes that had already begun long before luther with the onset of the renaissance. As important as luther was, one must be careful not to create a new myth here."

Bendikowski also warns against exaggerating luther and seeing only the positive aspects of the reformation anniversary. The "gruesome" consequences of the schism could not be concealed: "this new denominationalism within christianity is a geibel of modern times and not primarily a gain."